The Muslim Warrior Admired by Abraham Lincoln and Napoleon Bonaparte

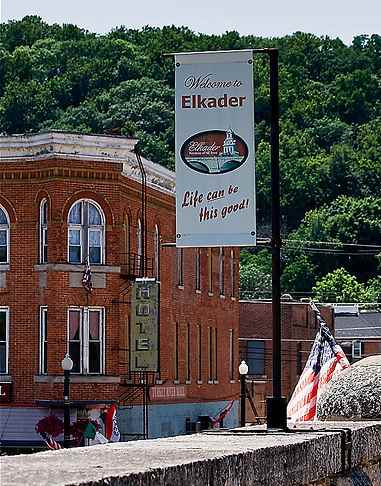

Emir Abd Elkader is unknown to most people in the west. He was a Muslim scholar, warrior and leader who earned the respect and praise of high figures of his time (1807-1883) such as Abraham Lincoln, the Pope, Napoleon Bonaparte III, Victor Hugo and Lord Londonderry. In 1846 Timothy Davis, John Thompson and Chester Sage were so impressed by his fight against French colonial power that they named their new settlement after him. The town of Elkader still bears the name of the emir and is located in Clayton County, Iowa.

Abd Elkader was born on September 6, 1808 to a devout Muslim family in Mascara, Algeria. When he was 22 years old, France invaded and occupied Algeria. The Algerians who were no match to the French Army, fought back ferociously. Two years into the occupation Abdelkader was chosen by the Algerian fighters to lead their armed resistance against the French.

To subdue the Algerian people the French commited countless atrocities. They were mutilating Algerian prisoners, severing heads and displaying them as trophies of war, wiping out entire villages, burning men, women, and children alive.

In the book “La chasse a l’homme” the French Count de Crisson writes “We would bring back a barrel full of ears harvested, pair by pair, from prisoners, friends or foes,”. In 1883 a French Government Inquiry Commission said: “We massacred people carrying [French] passes. On a suspicion we slit the throats of entire populations who were later on proven to be innocent; we tried men famous for their holiness in the land, venerated men, because they had enough courage to come and meet our rage in order to intercede on behalf of their unfortunate fellow countrymen.”

Abd Elkader led the resistance for 15 years and initially made great progress by liberating the western provinces of Algeria and setting up a state with its own currency “the muhammadiya” and administrative departments.

Despite the French army’s savagery Emir Abd Elkader fought within the confines of Islamic warfare, strictly adhering to its rules and principles. Long before the Geneva conventions of the treatment of prisoners of war, he issued the following edict: “Every Arab who captures alive a French soldier will receive as reward eight douros. Every Arab who has in his possession a Frenchman is bound to treat him well and to take him to either his commander or the Emir himself, as soon as possible. In cases where the prisoner complains of ill treatment, the Arab will have no right to any reward.” When asked what the reward was for a severed French head, the Emir replied “twenty-five blows of the baton on the soles of the feet”.

Abd Elkader made sure his prisoners were protected against violent reprisals on the part of outraged tribesmen seeking to avenge loved ones. He also invited a Christian priest to minister to their religious needs. In a letter to Dupuch, Bishop of Algeria, with whom he had entered into negotiations regarding prisoners generally, he wrote “Send a priest to my camp, he will lack nothing”. In one instance he even freed prisoners when he did not have enough food for them.

Likewise, as regards female prisoners, he exercised the most sensitive treatment, having them placed under the protective care of his mother, lodging them in a tent permanently guarded against any would be molesters. It is hardly surprising that some of these prisoners of war embraced Islam, while others, once they were freed, sought to remain with the Emir and serve under him.

The Emir’s humane treatment of French prisoners was kept secret from the French forces; had it leaked out, the result would have been devastating for the morale of the French forces, who had been told that they were fighting a war for the sake of civilization, and that their adversaries were barbarians. As Colonel Gery confided in the Bishop of Algeria, “We are obliged to try as hard as we can to hide these things [the treatment accorded French prisoners by the Emir] from our soldiers. For if they so much as suspected such things, they would not hasten with such fury against Abd el-Kader.”

After 15 years of fierce resistance against one of the most advanced armies of the time, the emir was at last defeated and in 1847 he negotiated his surrender in exchange for exile in Egypt. But the French didn’t keep their word and instead sent him to prison in France. There he learned French and studied the works of Greek and Muslim philosophers. He later wrote his first book “Call to the Intelligent”. Hundreds of French admirers who had heard of his bravery and his nobility visited him and he was most deeply touched by the French officers who came to thank him for the treatment they received at his hands when they were his prisoners in Algeria.

A few years later he was exiled to Damascus and on a day of July 1860 his true character was again tested. The civil war that was raging in Lebanon had reached Damascus and the Christian population found themselves surrounded by the Syrian Druze who arrived brandishing swords and knives determined to slaughter them all.

The French newspaper ‘Le Siecle’ on 2 August 1869 documented what happened on that day “We were in consternation, all of us quite convinced that our last hour had arrived. In that expectation of death, in those indescribable moments of anguish, Heaven, however, sent us a savior! Abd el-Kader appeared, surrounded by his Algerians, around forty of them. He was on horseback and without arms: his handsome figure calm and imposing made a strange contrast with the noise and disorder that reigned everywhere. For five days and nights he and his band of Algerians neither slept nor rested, battling out in the streets and guiding Christians to his large mansion where they could dwell in safety. By the time they were finished, they had managed to save over 15,000 Christians, the majority of which were the very same European people who had colonized his native land and were in the process of colonizing others. An Arab leader had, with his life, protected and saved the elite of Europe.”

When France later bestowed on him its highest honor, the “Legion D’honneur” he said: “The good that we did to the Christians was what we were obliged to do, out of fidelity to Islamic law and out of respect for the rights of humanity. For all creatures are the family of God, and those most beloved of God are those who are most beneficial to his family.”